I struggled a bit with the whole “pastis” idea. I enjoy the flavor of anise, and like the flavor in cocktails, but when looking for a pastis-containing drink that had an agreeable taste, and that had a decent story, I kept running into dead-ends.

I struggled a bit with the whole “pastis” idea. I enjoy the flavor of anise, and like the flavor in cocktails, but when looking for a pastis-containing drink that had an agreeable taste, and that had a decent story, I kept running into dead-ends.

Then I came across the cannibals.

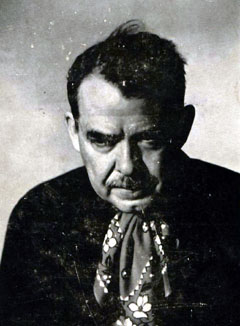

William Seabrook was an old-school adventurer. A Maryland native, Seabrook fought for the French army during World War I (and was gassed at Verdun), then started a career as a newspaper reporter. After a few years writing for Hearst papers, Seabrook embarked on a freelance career, writing for publications including Vanity Fair and Reader’s Digest, and quickly earned a reputation as an intrepid traveler who would venture into the unknown for months on end, go deep with the locals, and come back with an incredible story.

His first book, Adventures in Arabia: Among the Bedouins, Druses, Whirling Dervishes & Yezidee Devil Worshippers, was published in 1928 (and republished as recently as 1991). The Magic Island, an account of his months spent in Haiti–during which Seabrook became possibly the first journalist to witness and document voodoo rituals in the island nation’s cities and remote villages–followed in 1929. In 1931, Seabrook shocked readers with Jungle Ways, in which he documented his journey across Africa, from Ivory Coast to Timbuktu, at one point spending several months living with cannibalistic tribes and, he claimed, once dining on human flesh (a claim he later withdrew, after realizing years later that his hosts–possibly repelled by his distasteful display of enthusiasm–had probably duped him with a meal of roast gorilla*). Throughout these travels and the popular books they spawned, Seabrook revealed himself to be a keen student of anthropology, with a special interest in native religion, mysticism, sorcery and magic.

His first book, Adventures in Arabia: Among the Bedouins, Druses, Whirling Dervishes & Yezidee Devil Worshippers, was published in 1928 (and republished as recently as 1991). The Magic Island, an account of his months spent in Haiti–during which Seabrook became possibly the first journalist to witness and document voodoo rituals in the island nation’s cities and remote villages–followed in 1929. In 1931, Seabrook shocked readers with Jungle Ways, in which he documented his journey across Africa, from Ivory Coast to Timbuktu, at one point spending several months living with cannibalistic tribes and, he claimed, once dining on human flesh (a claim he later withdrew, after realizing years later that his hosts–possibly repelled by his distasteful display of enthusiasm–had probably duped him with a meal of roast gorilla*). Throughout these travels and the popular books they spawned, Seabrook revealed himself to be a keen student of anthropology, with a special interest in native religion, mysticism, sorcery and magic.

Seabrook’s adventures and success as an author earned him access to intriguing circles in Paris and New York. He counted the photographer Man Ray among his friendly acquaintances, and the noted occultist Aleister Crowley was one of his closest friends (and, later, one of his most bitter enemies). Reporter, adventurer, writer, sorcery aficionado and self-professed sadist and masochist, Seabrook was a complicated man.

He was also a world-class lush.

In the early 1930s Seabrook was, by his own estimation, knocking back a quart to a quart-and-a-half of Scotch, gin, brandy and Pernod every day. By 1933, disgusted that he had become a drunkard of the tumbler-of-whiskey-before-getting-out-of-bed variety, Seabrook and his friends decided he needed serious help. On December 4–the night before Prohibition was repealed– Seabrook sought treatment for chronic alcoholism and had himself committed to an insane asylum in Westchester County, north of New York City. He stayed there for seven months, a lone souse in a ward full of schizophrenics, manic-depressives, catatonics and hysterics. He recounted his experiences in 1935 in Asylum, perhaps the first published inside account of a patient in a mental institution, and a milestone in the literature of the treatment of alcoholism. A mild bestseller, Asylum was reprinted in several pulp paperback editions through the 1960s.

Seabrook’s treatment took place at a time just after straightjackets and handcuffs had been removed from regular use, but his experience was still quite severe. After sleeping off his final drunk, Seabrook was examined by doctors, shaved, and then taken to be bathed.

Seabrook’s treatment took place at a time just after straightjackets and handcuffs had been removed from regular use, but his experience was still quite severe. After sleeping off his final drunk, Seabrook was examined by doctors, shaved, and then taken to be bathed.

[…]A fireman stood behind two hoseless nozzles, mounted on a fireboat pedestal with dials and gauges. They stripped me and stood me against the wall where I’d make a fine target, with bars to cling to, so that I wouldn’t be knocked down. They gave it to me, first hot, then cold, then hot and cold together. I let out several loud howls, and they laughed. I didn’t know whether I was howling because I enjoyed it or because I was outraged. It hit you sometimes like a fist. It was like having a barroom fight with the Johnstown flood.

After being bound to his bed with layers of wet sheets while he sweated through the DTs, Seabrook gradually settled into life in the institution. He made friends with the other patients; squabbled with the staff (particularly over the subject of prunes), and, eventually, came to believe he was completely cured of his chronic alcoholism.

Following his discharge, and the publication of Asylum, Seabrook did the only sensible thing for a recently reformed drunk: he contributed a drink recipe to a novelty cocktail manual.

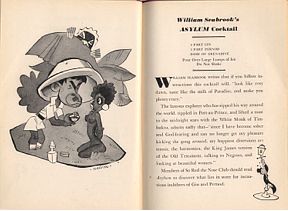

So Red the Nose, or Breath in the Afternoon is a 1935 compilation of 30 cocktail recipes (each accompanied by an illustration, several–including the one for Seabrook’s page–blatantly offensive in a racial-and-ethnic-charicature kind of way), submitted by some of the leading authors of the day. Participating authors included Erskine Caldwell, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Theodore Dreiser and Ernest Hemingway, who contributed perhaps the book’s most famous concoction, Death in the Afternoon, his legendary absinthe-and-champagne gloom-lifter. Seabrook’s drink was the Asylum Cocktail, which, as he described, can “look like rosy dawn, taste like the milk of Paradise, and make you plenty crazy.”

So Red the Nose, or Breath in the Afternoon is a 1935 compilation of 30 cocktail recipes (each accompanied by an illustration, several–including the one for Seabrook’s page–blatantly offensive in a racial-and-ethnic-charicature kind of way), submitted by some of the leading authors of the day. Participating authors included Erskine Caldwell, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Theodore Dreiser and Ernest Hemingway, who contributed perhaps the book’s most famous concoction, Death in the Afternoon, his legendary absinthe-and-champagne gloom-lifter. Seabrook’s drink was the Asylum Cocktail, which, as he described, can “look like rosy dawn, taste like the milk of Paradise, and make you plenty crazy.”

Composed of equal parts gin and Pernod, with a touch of grenadine for color, the Asylum resembles no dawn I’ve ever seen, unless it’s one I’ve forgotten due to the preceding evening and its resulting alcohol fog–which probably explains where Seabrook’s description comes in. The Asylum isn’t the best pastis-containing cocktail out there, but it’s also not the worst. When something comes recommended from a man with a hankering for human flesh and a habit of hobnobbing with devil-worshippers, it sometimes pays to experiment a little. But caution is warranted: as the editors of the volume note, “Members of So Red the Nose Club should read Asylum to discover what lies in store for incautious imbibers of Gin and Pernod.”

Asylum Cocktail

- 1 1/2 ounces gin

- 1 1/2 ounces Pernod

- 1 teaspoon grenadine

In a rocks or Old Fashioned glass, build the grenadine, Pernod (or other anise-flavored liqueur) and gin, in that order; do not stir. Gently add ice; watch as the cocktail changes colors. Eventually drink.

[Oh, and Seabrook? A lush for life, as he relates in his autobiography, No Hiding Place, published in 1942, two years before he took his own life with an overdose of sleeping pills.]

When mixing the Asylum, or any other cocktail calling for a pastis or absinthe substitute, there are a range of available options. Pernod, the most popular anise-flavored liqueur, works quite well in these drinks–though, with its grape-alcohol base, Pernod is technically not a pastis (by definition, pastis is made with a neutral alcohol base; but what the hell–Pernod works, and it’s easy to find).

It’s worthwhile to venture beyond the most familiar products on the shelf. Thanks to Murray at Zig Zag, I had the chance to sample a few true pastis last week. My favorite of the group was Granier, which had an assertive anise aroma yet was soft and well-rounded in flavor, slightly sweet, and retained its character when mixed with water. Others, such as the more-familiar Ricard–which presented the sweetness first and the anise in a short, coarse burst afterward–and La Muse Verte–an unsweetened pastis that tasted crisp and bright neat, with a touch of bitterness, yet folded quickly when mixed with water–fell further down on my list.

* UPDATE: Promoted from the comments section, Adam Thornton helpfully points out that Seabrook did consume human flesh–though not with the African tribe, as he initially thought, but rather, later on, in Paris. Realizing he lacked the necessary experience to write about cannibalism, Seabrook convinced a friend at a morgue to give him a piece of flesh from an accident victim, then carefully prepared it in his kitchen, documenting every step.

Read Adam’s comment and follow the link to get the full, um, flavor of Seabrook’s endeavor. And if you’ll now excuse me, I have a topic to propose over at “Is My Blog Burning?”

Wow, Paul, this was a really interesting read! I did a quick search for the cocktail book but found it for no less than $50 (except for one fire-survived version). Is it worth it?

So far, Mixology Monday is really looking good. I must admit, I’m a bit frightened to try some of these pastis cocktails. What better reason not to then, right?

Not really. So Red the Nose is pretty much just a novelty, and a dated one at that–from a mixological standpoint, few of the cocktails are worthy of even being tried, much less resurrected. But as a period piece, it’s pretty interesting–if you can find it for under, oh, $20, and you’re into that kind of thing, I’d say go for it.

Seabrook probably *did* eat human flesh, as it turns out.

The tale is told in Gary Allen’s paper:

http://food.oregonstate.edu/ref/culture/taboo_allen.html

Turns out Long Pig doesn’t taste like pork at all. Tastes like veal.

Bon appetit!

Adam

[…] Anyway, before I got sidetracked by creme de menthe I was going to give a shout for the Bunnyhug. For some reason everybody hates this drink. I admit the Bunnyhug has a rough edge or two, and perhaps my palate could be more refined, but really, for pure abrasive flavorsomeness this drink has few equals. Another drink that comes close is the Asylum Cocktail. […]