There are few compounds that are more sinful than the applejack of New Jersey. The name has a homely, innocent appearance, but in reality applejack is a particularly powerful and evil spirit. The man who intoxicates himself on bad whisky is sometimes moved to kill his wife and set his house on fire, but the victim of applejack is capable of blowing up a whole town with dynamite and of reciting original poetry to every surviving inhabitant.

— “A Wicked Beverage,†New York Times, April 10, 1894

You can learn a lot about a civilization by looking at what it drinks — and when that civilization is an early ancestor of your own, an exploration of the drinking habits can result in not only an interesting anecdote or two, but hopefully a better picture of who we are as a society.

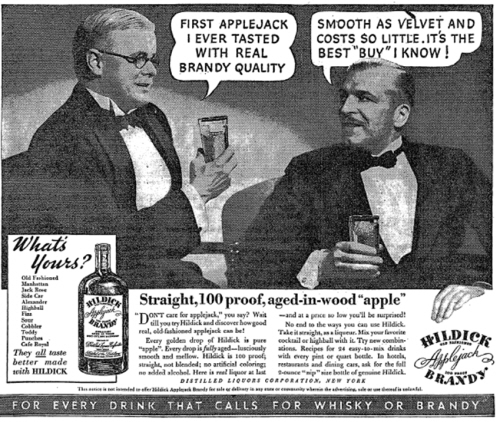

In our early years, Americans drank pretty much anything that was available — but “available†is the operative term here. Our ancestors drank beer and wine, when it was available, which after the initial supplies ran out, wasn’t very often; soon, brandy and, more importantly, rum entered the picture, and eventually whiskey worked its way into the mix. But for much of America’s history, from the earliest Colonial days and for the more than two centuries that followed, Americans sated their thirst for beverages that conveyed a buzz mostly with libations that came from the fruit of the apple tree — primarily in the form of hard cider, which was EVERYWHERE and in tremendous quantities, but also in its harder, sharper and, at times, burly and boisterous relative: applejack, the distinctive American interpretation of apple brandy.

For a drink that so enamored our American ancestors (especially in the Northeast), we know awfully little about applejack and American apple brandy today. If your reading habits have brought you to this blog, you’re no doubt already familiar with Laird’s applejack and probably their bonded apple brandy, too, and you may even know of newer, small-scale producers somewhere (legal or, um, “artisanalâ€) who are making the stuff. But what else do you know about American apple brandy?

The answer, probably, is “not much.†A year or so ago, I was lamenting my own ignorance of a category that I still found pretty fascinating, so I started putting together bits of historical info that eventually made their way into my “As American as Apple Brandy†presentation at Tales of the Cocktail in July (where I was joined by another ardent fan of apple brandy, my good friend Misty Kalkofen, from Drink in Boston).

In case you missed my applejack schtick at Tales, there’s another opportunity coming up where you can see me get way too excited about this style of spirit that’s undergoing a bit of a comeback: on Saturday, November 19, I’ll be talking about American apple brandy as part of Swig Well: Seattle Drinking Academy, at Rob Roy.

Among the things I’ll babble about are bits of apple-brandy history such as:

- In 1830, near the end of the farmstead epoch of American distilling, there were 430 distillers operating in New Jersey. Even after liquor production moved primarily to large, centralized distilleries, there were still approximately 60 distilleries in southern New York producing apple brandy in 1890, and in 1892, more than 70 distilleries in New Jersey produced around 13,000 barrels of the stuff.

- Long ignored by the temperance movement, apple growers eventually came under Prohibitionist assault around the turn of the 20th century. The result? Thousands of apple trees were destroyed to disrupt the production of cider; facing this threat, apple growers embraced what became one of history’s most memorable marketing slogans: “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

- In anticipation of the demand that would follow Prohibition’s repeal, Laird’s & Co. announced in October, 1933, that they’d begun production of 1 million gallons of apple brandy—“for medicinal purposes.”

Oh — and there’ll be cocktails.

Oh — and there’ll be cocktails.

This is my first scheduled class at Swig Well, and while tickets are limited, I want to make sure every seat is full. The class is an hour-ish long (I get chatty sometimes), and takes place on the afternoon of Saturday, November 19 (I don’t have a set start time yet, but it’ll be between noon and 3pm) from 1:30pm to 2:30pm; tickets are $75 each.

Check out my original post about Swig Well, then head over to their site to see the syllabus and to sign up for tickets (you’ll need advance reservations — like I said, tickets are limited). And, while you’re at it, check them out on your social-media platform of choice: Swig Well on Twitter, and Swig Well on Facebook.